Homelessness in South Los Angeles - Marqueece Harris-Dawson (2)

Following is a position paper on homelessness in South Los Angeles issued in February 2016 by Marqueece Harris-Dawson, Los Angeles City Council member for District 8 in South Los Angeles. He is co-chair of the City Council's Homelessness and Poverty Committee. We have retained the source notes at the end but they do not hotlink to the main text. A downloadable PDF of this document is available HERE.

* * *

Homelessness in South Los Angeles

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The primary purpose of this paper is to provide a thorough understanding of homelessness in Los Angeles as it pertains to the Eighth City Council District and South Los Angeles more broadly. On January 13, 2016, the City of Los Angeles released a Comprehensive Homeless Strategy detailing over 60 strategies to combat homelessness. The citywide view is sweeping, expansive, and comprehensive, but falls short when detailing the geographic and demographic particularities of South Los Angeles. While I support implementation of all strategies within the Comprehensive Homeless

Strategy for Los Angeles, there are specific social,

economic, and housing policies at the local, state, and federal levels that require focused attention in order to adequately address the vulnerable subset of the homeless population. Without a deep analysis of the root causes of homelessness and the particular issues in South Los Angeles, the Comprehensive Homeless Strategy may miss key opportunities to have a measurable reduction in the flow of individuals entering homelessness.

The current homelessness crisis is decades in the making. For nearly 60 years, policies at every level of government have contributed to a disappearing social safety net, the loss of affordable housing, the rise of mass incarceration, the reduction of middle class jobs, and the destruction of public mental health care.

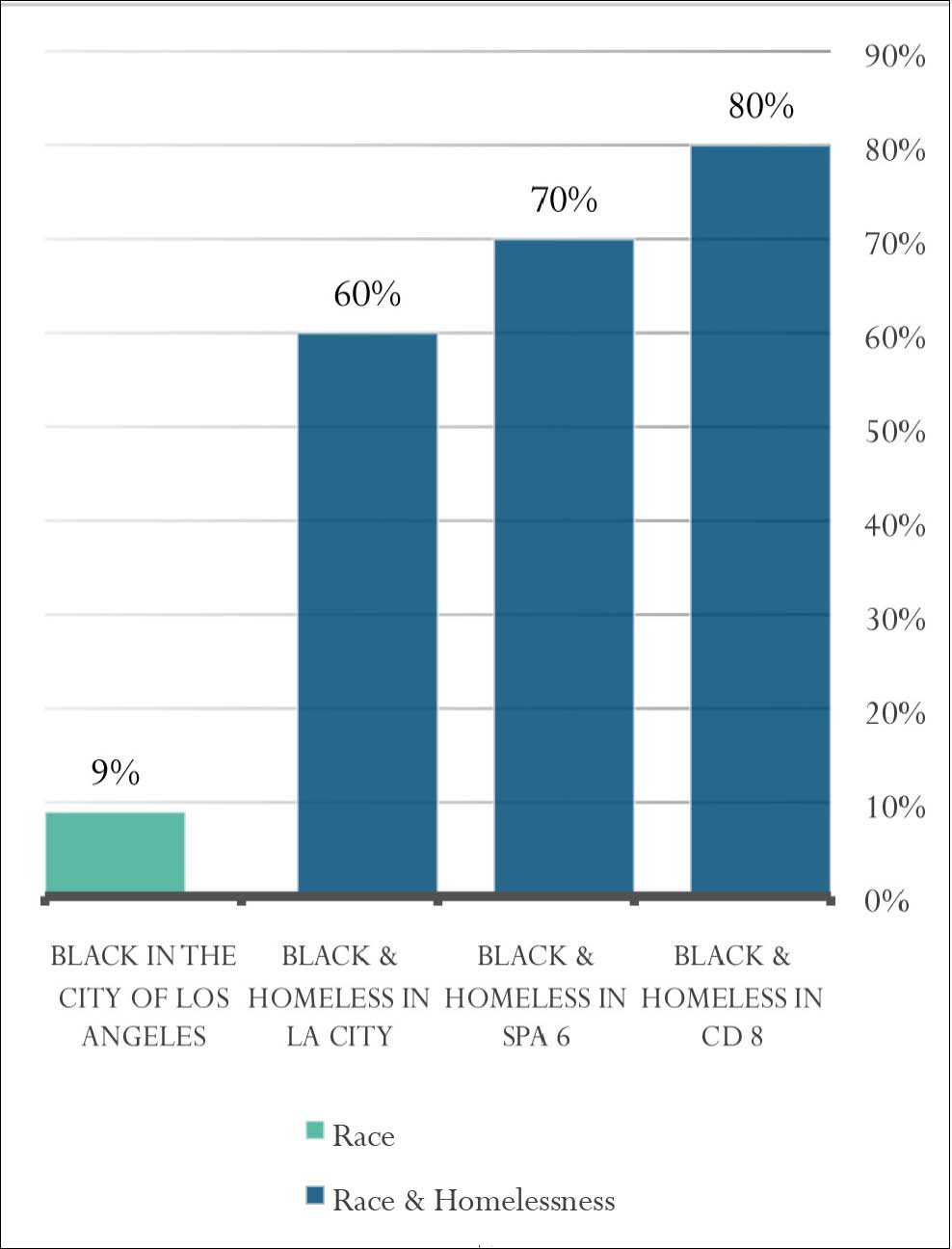

Upon examining the homelessness crisis more closely, the striking demographic trend among the homeless population in Los Angeles is that of race. Throughout the City, but extraordinarily in South Los Angeles and on Skid Row, the face of homelessness is most often a Black one. In Los Angeles, 9 percent of the population is Black, however, Black people make up an astonishing 47 percent of the homeless population. Taken together, South LA and Skid Row account for over 40 percent of all homeless people in City of Los Angeles and 53 percent of those homeless individuals are Black. Analysis from the Special Services Group argues that “while the high concentration of the homeless in Skid Row can be explained by the presence of services and beds, the large homeless population in South LA is explained by poor economic and social conditions.”i These poor conditions are amplified for Black individuals and families. Discrimination, both overt and systematic, has limited opportunities for good jobs, adequate housing, and financial security. The Great Recession added to that trend nationally, with Black unemployment skyrocketing to 16.7 percent at its height.ii Even as other families have seen some gains in employment and average wages, Black families have continued to suffer, with Black unemployment remaining at double that of white unemployment.iii

The City of Los Angeles must produce tens of thousands of affordable and subsidized housing units in order to meet the demands of the population. Additionally, in order to preserve the existing housing stock, we must review, analyze, and amend harmful land use policies that undermine the City’s ability to sustain affordable rental units. The production of needed affordable housing units and the provision of supportive services for over 25,000 homeless individuals is unattainable without an infusion of federal dollars to support all types of housing vouchers including veterans, rapid re-housing and Section 8. Additionally, without relief from relentless cuts to anti-poverty programs such as direct aid to needy families, more families will be pushed into homelessness.

Mental health is another serious challenge afflicting a large swath of homeless individuals, particularly so in South Los Angeles. A sparse public mental health system throughout the state leaves individuals with limited access to professional medical assistance, recuperative beds, or hospitalization, which further increases the amount of individuals falling into chronic homelessness.

The final antecedent that has devastated the residents of South Los Angeles is discriminatory policing and sentencing policies otherwise known as the “War on Drugs”. Racialized sentencing for nonviolent drug offenses has produced a disproportionate concentration of Black men and women in the prison system. A compounding factor is the limited substance abuse and mental health services, job training, housing assistance, or other services necessary for successful reentry. Often individuals reenter society in a worse position than when they entered the criminal justice system.

As is evident, the City cannot achieve a reduction of homelessness unilaterally. It is only through sustained coordination with my counterparts in the County, State and Federal levels that we will be able to substantially decrease the flow of individuals into homelessness.

INTRODUCTION

The City of Los Angeles is faced with an untenable level of homelessness and we must take action to stem the tide. It is vital that we understand the history and root causes of homelessness in order to make effective policy decisions. Individuals that suffer from mental illness and substance abuse are often discussed as being at high risk for homelessness, yet, victims of domestic violence, youth in the foster care system, and Black residents who are also at a high risk, do not get the same attention. In truth, poverty is the biggest risk factor for homelessness.iV Only by identifying those most impacted and the needs of those most vulnerable to homelessness will intervention be successfully targeted. Neither money without strategy nor gimmicks without substance will bring change to the lives of over 44,000 homeless individuals and families living on the streets or in shelters in Los Angeles County which has the second largest homeless population in the U.S. v

Neither money without strategy, nor gimmicks without substance, will bring change to the lives of over 44,000 homeless individuals and families living on the streets or in shelters in Los Angeles County, the second largest homeless population in the U.S.

Research suggests that 13,300 recipients of social services in Los Angeles County become homeless every month.vi Approximately, 11,200 residents also exit homelessness and that gap indicates a steady flow of individuals into homelessness every month. The City must address the antecedents of homelessness and provide substantive resources in order to have a more significant impact than it currently does. Only when the root causes of homelessness are targeted, such as lack of good wages, lack of affordable housing, lack of availability of subsidies and social services, racial and economic discrimination, and lack of support for victims of domestic violence and transitional age youth, can we begin to see an enduring transformation. Today, there are political, social service, homeless, formerly homeless and activist collaborators, who together can create the conditions necessary to impact the lives of homeless families, individuals, and youth. However, it will take sustained and strategic investments to see a substantial change.

HISTORY

Homelessness as we know it today began in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Prior to this time the United States provided a greater share of social welfare, support for unions, and institutions supporting the poor.vii Over 30 years of federal policies such as the Wagner Act, the Works Progress Administration, the Social Security Administration, the creation of the Housing Authority, and the Fair Labor Standards Act stitched together the fabric of a safety net. However, with the War on Poverty declared “won” near the end of the 1960s, there was a dramatic ideological shift towards a new form of global capitalism and the fabrication of a narrative that stigmatized “public dependency,” disparaged poverty, and necessitated personal responsibility to the detriment of community or public responsibility.viii When the narrative centers on work as the primary indicator of human dignity, people in poverty become the problem, not poverty itself. Rapid deindustrialization in the 1970s and the decline of private sector unions meant the end of a middle class lifestyle for thousands of families, particularly Black families. Moreover, the decline of the public workforce, privatization of public services, deregulation, and jobs shifting overseas made full-time, family-sustaining jobs unattainable for many. The decline of the middle class has continued to present day and by 2015, middle class families no longer constituted the majority of Americans.ix

Modern homelessness was preceded by the elimination of mental institutions and the eradication of public mental health care nationwide. “In California, for example, the number of patients in state mental hospitals reached a peak of 37,500 in 1959 when Edmund G. Brown was Governor [and] fell to 22,000 when Ronald Reagan attained that of fice in 1967, and continued to decline under his administration.”x Today that number is less than 6,500.xi Historians posit that doctors promised a medical cure, including tranquilizers and antibiotics that could eliminate mental illness.xii Politicians quickly rid the state of its responsibility to care for individuals, opting instead to champion ‘community clinics’ as a low-cost solution to care.xiii Funding for community clinics soon vanished and the disappearance of public mental health care led many to self-medicate, which pushed them onto the streets or in a new institution: prisons.

Additionally, the decline of single room housing, namely single-room occupancy (SRO) units, roaming houses, and residential hotels, fundamentally shifted the nature of housing for poor individuals, childless couples, and families.xiv Single room housing often provided the only option for the disabled, the elderly, people with drug addictions, previously incarcerated individuals, and those discharged from hospitals and mental institutions. Research at Stanford confirms that “in 1970 there was a surplus of approximately 2.4 million low income units in America, by 1985 there was an estimated deficit of 3.7 million.”xv Today, there are only 28 units for every 100 extremely low income household, a deficit of 8.1 million units.xvi

Los Angeles only has 17.7 units for every 100 extremely low income households.xvi SROs are often referred to as a “housing of last resort,” and with the elimination of this housing option for more profitable forms of development, the housing of last resort has shifted to the streets.

Beginning in the 1980s, service providers, advocates, reporters, and social workers noted a substantial increase of people living on the streets with no other options.xviii Thus, the modern-day homelessness crisis began. As of 2015, according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development, nearly 565,000 people are homeless nationwide.xix Today, one in five homeless individuals live in Los Angeles or New York.xx Los Angeles has the highest number of unsheltered homeless individuals of any city in the country.xxi The question of how Los Angeles became the “unsheltered homeless capital of the United States” is complex, yet only by understanding these complexities can we begin to make substantive change.

CONTEMPORARY HISTORY

Housing & Foreclosures

The housing crisis in Los Angeles is not a new or sudden phenomenon. Citywide, there is a legacy of planned scarcity. Between 1940 and 1970 the number of housing units in California’s coastal communities, including Los Angeles, grew by 200 percent. Over the next 30 years, between 1980 and 2010, construction of new housing units grew by only around 20 percent.xxii This dramatic slow-down caused the cost of housing to rise substantially, making homes and rental properties in Los Angeles 50% higher than the rest of the nation.xxiii Today, the vacancy rate for apartments in Los Angeles is 3.3%, lower than New York City.xxiv Recent research suggests that a family needs to earn at least $33 an hourxxv — $68,640 a year —in order to afford the average apartment in Los Angeles County. That is more than triple the current minimum wage and more than double the $15 minimum wage passed by the City of Los Angeles in 2015.xxvi Only approximately 50% of Los Angeles County households make enough.xxvii

In addition to the slow-down of new home construction, there was a remarkable reduction in the number of SRO units, namely within the community of Skid Row. In Los Angeles, the Skid Row community can trace its origins to the 1870s when the development of railroads near the LA River necessitated an influx of workers to fill jobs in the newly industrial Central City East.xxviii Between the 1880s and 1930s, small residential hotels were constructed to house industrial and displaced workers from across the United States. Beginning in the Depression era, the numbers of displaced workers and poor increased in Skid Row as many moved west in the hope of finding work. Through the end of World War II, the Skid Row community grew to include businesses like bars, religious missions, brothels, and restaurants. The 1950s signaled major changes for the residential hotels of Skid Row. Between 1950 and 2000, nearly 15,000 residential hotel apartments were destroyed in favor of new development.xxix Only the Wiggins settlement, which forced the Community Redevelopment Agency maintain and/or replace single occupancy units that were destroyed by the redevelopment of Central City East, allowed some units to survive.xxx Today, only 6,500 of the original residential apartment units remain.xxxi The displacement of the largest source of SRO units decimated the number of affordable units in the city.

In addition to planned scarcity of housing and the displacement of residents who used SROs, two pieces of legislation and one appellate court decision limited the role that governments could play to ensure housing affordability. In 1995, AB 1164, also known as Costa-Hawkins, established that landlords have the ability to set rental rates on units when they change tenancy. Although renters in Los Angeles who live in apartments built before 1978 enjoy limitation on rent increases, once a tenant moves out, the owner has the ability to set a new rental rate that is not subject to such limitation. Additionally, the Ellis Act of 1985 allows landlords to evict all tenants from a rent controlled building and convert the units to market rate under certain conditions. In tandem, Costa-Hawkins and the Ellis Act provide for a legal framework that weakens the city’s ability to generate housing to meet the greater needs of the city.

Most recently, the Great Recession also dramatically shifted the housing market in the City of Los Angeles. The foreclosure crisis pushed homeowners out of their homes and evicted renters from properties where the owners were foreclosed upon. This compressed the rental market and added pressure from every side. In Los Angeles, the foreclosure rate jumped 800 percent, with some parts of Los Angeles seeing 1000 percent increases in foreclosures by 2007.xxxii The previous three decades of stalled housing construction combined with the foreclosure crisis created the perfect storm of unaffordability and scarcity. The dissolution of Community Redevelopment Agencies in 2011 to close budget deficits at the State level left Los Angeles without the financial resources needed to incentivize and support affordable housing. In the past, the CRA was able to utilize resources gathered through tax increment financing and land-use powers to leverage the creation of affordable housing in cities across California. However, the loss of this dedicated revenue stream has hampered the City’s ability to reverse the trend of stagnant housing growth and high rents.

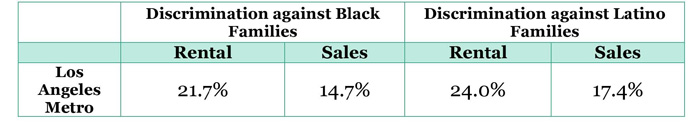

Housing discrimination is still a significant factor across the United States and magnifies planned scarcity in Los Angeles. In both the rental and home buyer markets, Black and Latino families still face multiple forms of housing discrimination. A nationwide study by the Department of Housing and Urban Development in 2000 found that in the Los Angeles Metro region, discrimination still impacted the housing searches of 22 and 24 percent of Black and Latino renters, respectively, and 15 and 17 percent of Black and Latino home buyers, respectively.xxxiii These percentages mirror national trends and represent an entrenched reality of discrimination for people of color. Renters of color are falsely told that rental units are no longer available, that they cannot inspect units, or are not given similar levels of assistance in completing applications or setting up future meetings as white prospective renters.xxxiv Home buyers of color are similarly faced with lack of access to inspect properties and failure to be given similar levels of assistance that are given to white home buyers. Additionally, home buyers of color face additional obstacles, such as being steered away from predominately white neighborhoods and given less information and assistance regarding financing options.xxxv

Housing discrimination is rarely discussed and is perceived to no longer be a problem, yet the subprime mortgage crisis reminded the nation that race is still a factor. In the aftermath of the Recession, two banks settled multi-million dollar lawsuits that alleged racial bias and discrimination against Black and Latino home buyers. Wells Fargo agreed to pay $175 million to settle claims that they “charged higher fees and rates to more than 30,000 minority borrowers across the country… [and] also steered more than 4,000 minority borrowers into more costly subprime mortgages when white borrowers with similar credit risk profiles had received regular loans.”xxvii Countrywide Financial Corporation agreed to pay $335 million to settle claims that they “charg[ed] more than 200,000 African-American and Hispanic borrowers higher fees and interest rates than non-Hispanic white borrowers in both its retail and wholesale lending.”xxxviii

Economy & Federal Spending

By far, poverty, low wages, wage theft, and the high cost of living are the biggest contributors to homelessness across the nation.xxxix Lack of employment, underemployment, and the prevalance of low wage work are constant drivers of poverty and economic insecurity. With constant economic insecurity, a single crisis can quickly drive an individual or a family into homelessness. For example, research from the Lawyer’s Committee on Civil Rights suggests that as many as 4 million Californians, more than 17% of adults, have suspended drivers licenses due to their inability to pay increased fines and limited access to the courts.xl In practice, this means one ticket can cascade into a loss of a license, limiting access to work, school, and civic activities. This is only one example of the ways economic insecurity puts the poor on the brink of homelessness.

Drug and alcohol abuse among homeless individuals is very complex and can be both the cause and the result of homelessness

During the Great Recession, homelessness actually decreased nationwide. President Obama devoted a one-time investment from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of $1.5 billion into housing vouchers for homeless veterans and for rapid re-housing, which quickly moves people out of shelters to limit the time they spend homeless.xli However, ARRA funding dried up at about the time that federal cuts to decrease the deficit began, which slashed domestic spending by approximately $1.1 trillion dollars through 2021.xlii Along with another round of cuts to the social safety net, these federal cuts eliminated the previous funding that was assembled by President George W. Bush, “[cutting] the number of Section 8 vouchers for affordable housing nationwide”. Homelessness is a lagging macroeconomic indicator, meaning that even when the economy contracts, homelessness doesn’t increase right away. It may take months or years for families to exhaust all their options. ARRA funding delayed the increase in homelessness temporarily, but federal cuts hastened it.

Mental Health & Substance Abuse

As discussed earlier, the closure of state mental hospitals has added to the homelessness crisis. In addition to the closure of most facilities, the policies that govern involuntary commitment have hampered the ability of the State to create any semblance of an integrated public mental health system. “In 1967, Gov. Ronald Reagan signed the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act (LPS), which went into effect in 1969 and quickly became a national model. Among other things, it prohibited forced medication or extended hospital stays without a judicial hearing.”xliv The LPS Act intended to provide people with severe mental illness or disability their deserved civil rights against unjust detention without due process. However, the stringent nature of the new policies regulating commitment made it impossible to stabilize someone in need of medication, with a mental health issue, or with severe substance abuse issues. Beginning in 1969, an individual could be held for 72 hours if they “engaged in an act of serious violence or demonstrated a likelihood of suicide or an inability to provide their own food, shelter or clothing due to mental illness…[And] only in extreme cases could someone be held another two weeks for evaluation and treatment.”xlv This victory for the rights of people with serious mental health issues, when seen in connection to the elimination of facilities and the failed promise of community clinics, swung the pendulum too far by eliminating the support structure of public mental health care.

Drug and alcohol abuse among homeless individuals is very complex and can be both the cause and the result of homelessness. Homeless individuals have higher incidences of co-occurring disorders, including mental health issues and acute and chronic medical conditions, like liver and cardiac disease, and tuberculosus.xlvi In fact, adults with disabilities are four times more likely to be living in a homeless shelter than an adult without a disability.xlvii In Los Angeles, 19% of homeless individuals have a physical disability, 24% struggle with substance abuse, and 32% suffer from mental illness.xlviii Individuals with severe drug problems and co-occurring disorders typically need longer treatment (e.g., a minimum of 3 months) and more comprehensive services.xlix “Homeless people with both substance abuse disorders and mental illness experience additional obstacles to recovery, such as increased risk for violence and victimization, and frequent cycling between the streets, jails, and emergency rooms.”l The best science indicates that substance abuse and serious mental illness require time, professional medical assistance, and for some, hospitalization, but the State has neither the beds nor the power to ensure that those in need of help have access.

War on Drugs & Mass Incarceration

Along with severe mental health issues and substance abuse, the “War on Drugs” has played a major role for many as an antecedent to homelessness. Instead of treating substance abuse as a health issue, the Nixon and the Reagan Administrations heavily criminalized and racialized the possession of drugs in the US in the 1970s and 1980s. “According to the Pew Center on the States, between 1973 and 2009, the nation’s prison population grew by 705 percent, resulting in more than 1 in 100 adults behind bars.”li Although the Nixon Administration began the “War on Drugs,” including passing mandatory minimum sentences for drug possession, it was the Reagan Administration that oversaw the dramatic expansion of the prison industrial complex that increased the number of people incarcerated for nonviolent drug offenses by 700 percent from 1980 to 1997. lii

Homelessness and incarceration are highly correlated and compounding issues that lead to a long cycle not easily escaped.

Most detrimentally, President Reagan targeted crack cocaine and Black people as the faces of his war. This has led to a long legacy of discriminatory policing and sentencing that targets Black men in the United States. Research established that “even though whites outnumber Blacks five to one and both groups use and sell drugs at similar rates, African-Americans comprise 35% of those arrested for drug possession; 55% of those convicted for drug possession; and 74% of those imprisoned for drug possession”liii. When people leave the criminal justice system, they are often at risk for homelessness, continued substance abuse, and mental health issues. Homelessness and incarceration are highly correlated and compounding issues that lead to a long cycle not easily escaped. Research demonstrates that “the number of people who lacked stable housing after being released from incarceration almost doubled, from 35 percent having unstable housing prior to their most recent incarceration to 63 percent 6 months after being released.”liv Those with conviction histories, who have paid their debt to society, face a mountain of challenges before successfully transitioning back to society, which increases recidivism rates and devastates families and communities.

DEMOGRAPHICS OF HOMELESSNESS IN SOUTH LOS ANGELES

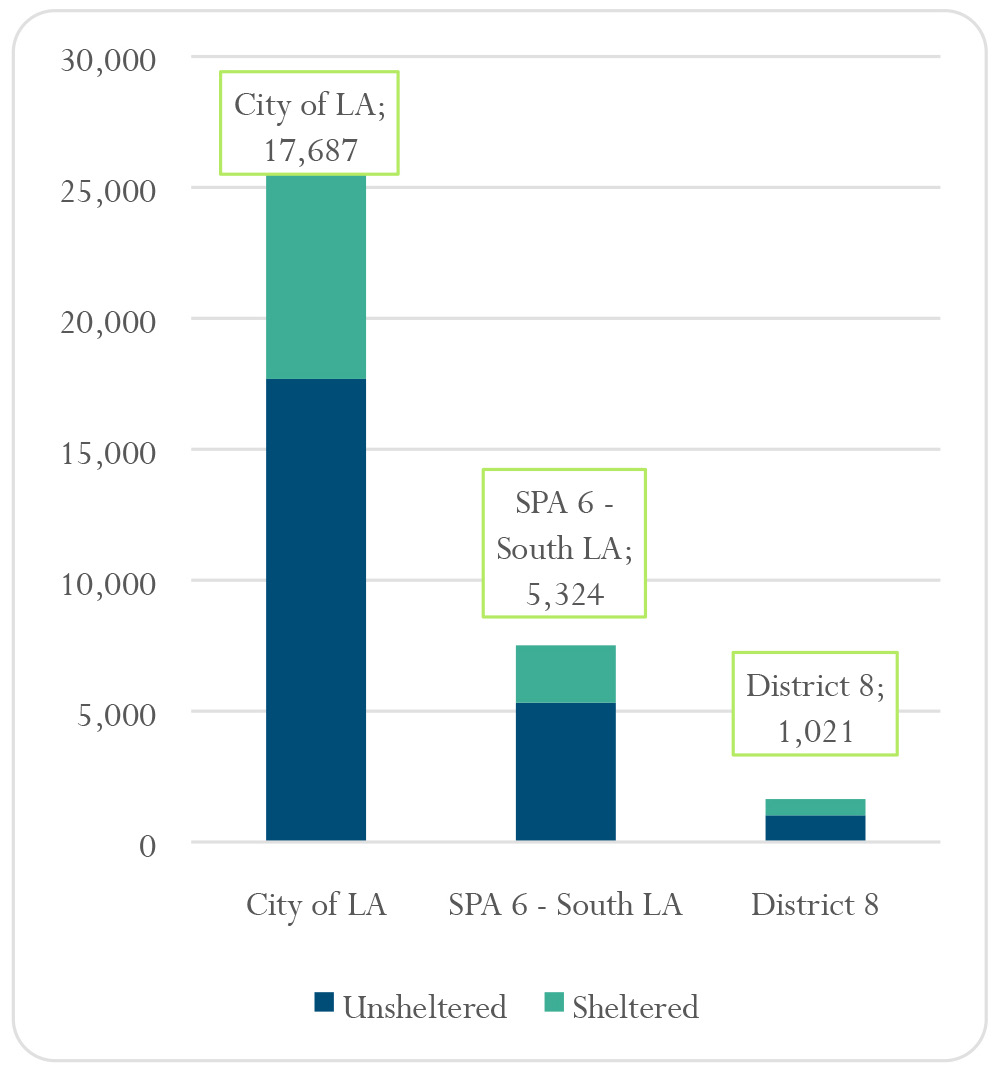

The Homeless Count is administered by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA) and provides a snapshot of the number and demographic characteristics of homeless individuals. The results of the 2015 Homeless Count found that across Los Angeles County, homelessness increased by 12 percent in the past two years and the number of unsheltered homeless persons increased by 33 percent over the past four years.lv In the City of Los Angeles, 70 percent of all homeless individuals are living on the streets.lvi In fact, Los Angeles has the greatest number of unsheltered homeless persons in the nation.lvii

FIGURE 2: SHELTERED AND UNSHELTERED HOMELESS PERSONS IN 2015lviii

“The number of tents, makeshift encampments, and vehicles occupied by homeless people soared 85%, to 9,535, according to biennial figures from the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority.”lix The increase in the number of tents in Los Angeles creates a visual reminder of homelessness and poverty on the streets that is impossible to ignore. Temperate weather may contribute to the high level of unsheltered homeless persons, but without any “Right to Shelter” laws nor adequate affordable housing, unsheltered homelessness in Los Angeles will continue.

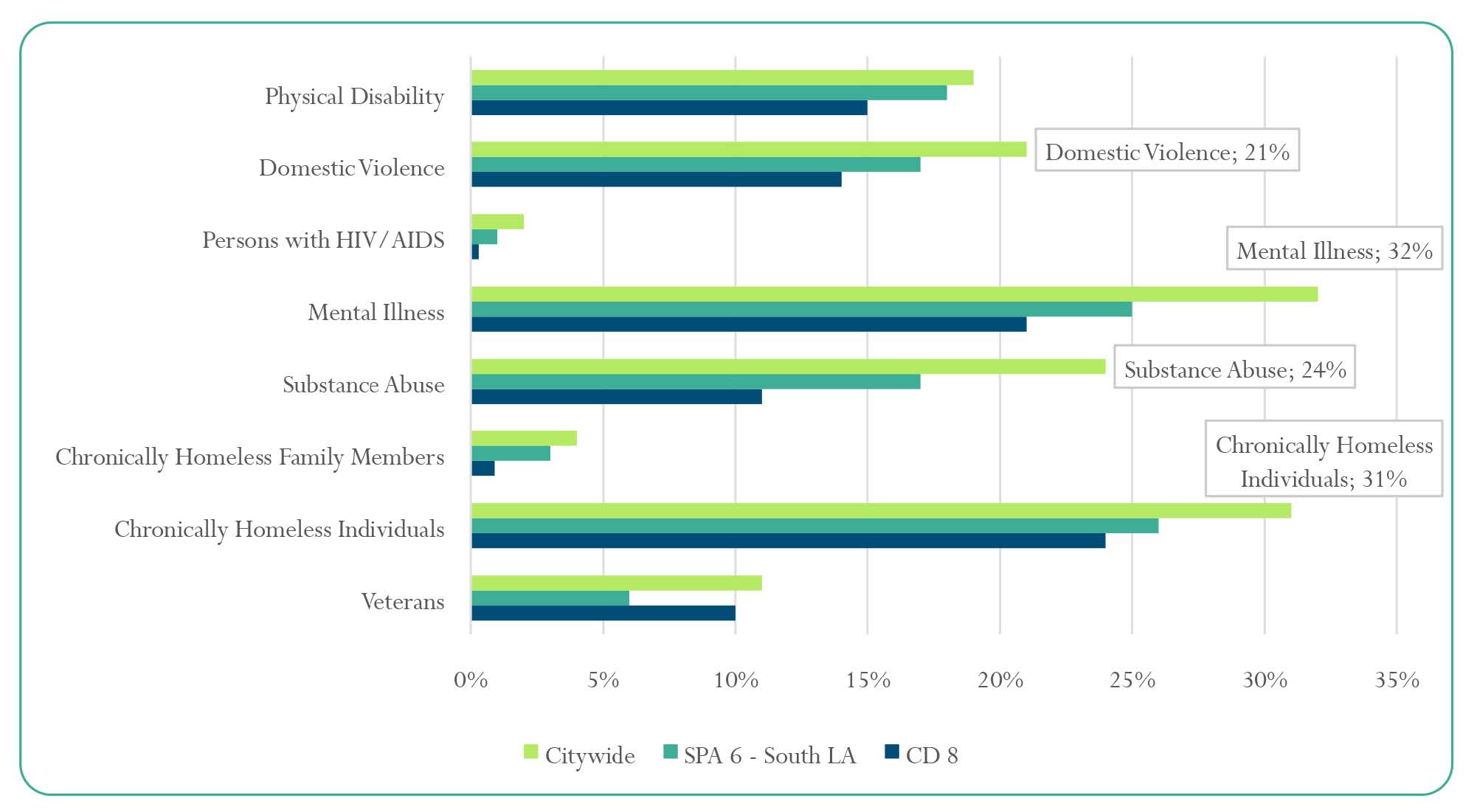

Looking deeper into the demographics of the homeless population, there are a few key indicators that point to troubling trends. Figure 2lx lays out some of the demographic characteristics of homeless persons across the City of Los Angeles, Service Planning Area 6 (SPA 6) which covers the broader South Los Angeles community (including cities other than Los Angeles), and City Council District 8. The largest two sub-populations are those experiencing mental illness and chronically homeless individuals. Citywide, 32 percent of homeless individuals suffer from mental health concerns which is at 76 percent higher rates than the rest of the population.lxii In the City of Los Angeles, 24 percent of homeless individuals struggle with substance abuse issues. These demographics are linked, as mental illness and substance abuse can cause chronic homelessness, and chronic homelessness can lead to mental illness and substance abuse.

In Los Angeles County, 33 percent of homeless individuals are womenlxvii, and without a focus on domestic violence, we are failing to serve a large portion of the homeless population.

FIGURE 3: DEMOGRAPHICS OF HOMELESS PERSONS IN LOS ANGELES

Another subset of this population that requires urgency and a unique solution is victims of domestic violence. In the City of Los Angeles, 21 percent of homeless individuals are victims of domestic violence. A study in nearby San Diego asserted that 50 percent of all homeless women were victims of domestic abuse and that abuse led directly to their homelessness.lxiii Another study indicated that "am many as 90 [percent] of homeless women have experienced severe physical or sexual abuse at some point in their lives."lxiv Domestic violence is the leading cause of homelessness for women, and nationally only 7 percent of homeless shelter beds are dedicated to serving victims of domestic violence, leading to a major service gap for homeless women.lxv Additionally, cities across the nation are seeing dedicated resources for transitional housing, a best practice for victims of domestic violence, disappearing based on the newest funding criteria from the US Housing and Urban Development Department.lxvi In Los Angeles County, 33 percent of homeless individuals are womenlxvii, and without a focus on domestic violence, we are failing to serve a large portion of the homeless population.

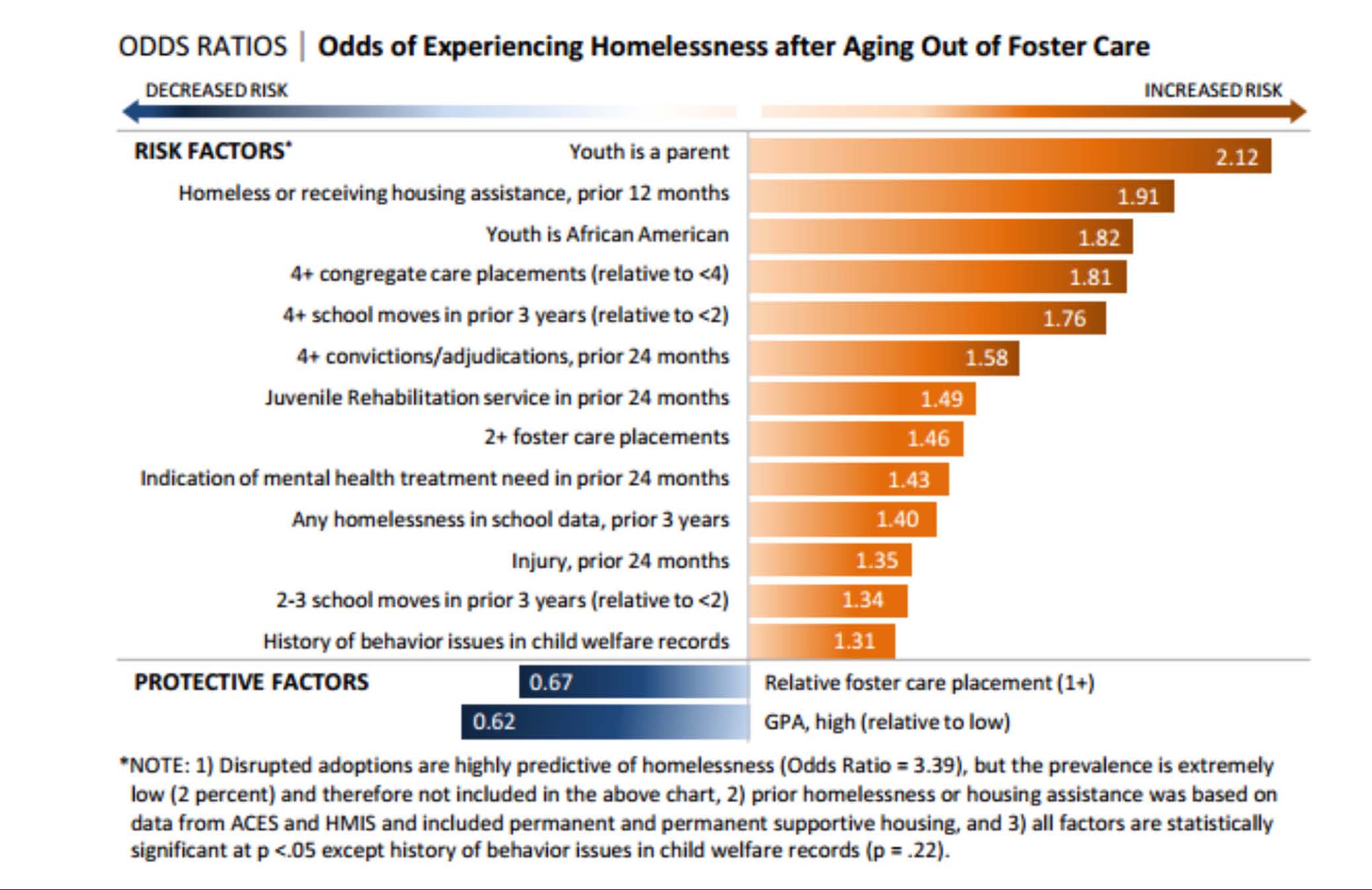

Youth are an additional demographic component that demonstrate the need for unique solutions. A count of homeless youth conducted by the Los Angeles County Office of Education provided a broader snapshot of homeless youth. Their definition of homelessness was broader than LAHSA's and they estimated that 31,802 students were either in a shelter, unsheltered, living in a hotel/motel, or "doubled up". The causes of youth homelessness are similar to the causes of homelessness in the adult populationi, yet, we see the striking impact of the foster care system. Research at the University of Chicago asserted that by age 26, 36% of young people in the foster care system will experience at least one episode of homelessness.lxx Furthermore, the odds of a young person experiencing homelessness after emancipation from the foster care system nearly doubles when the are a parent, were homeless in the previous two months, or they are Black.lxxi We must focus on targeted solutions for foster youth to ensure they do not b3ecome homeless or chronically homeless adults.

In Council District 8, there was a 29 percent decrease in homelessness over the past two years. However, even as homelessness decreased, the percentage of Black homeless people actually increased. In 2013, approximately 923 homeless indiviudals were Black.lxxiii By 2015, 1,313 homeless individuals were Black. That is a 42 percent increase in Black homelessness in the district in two years.lxxiv Across the City of Los Angeles in 2015, Black homelessness increased by 35 percent from 2013, while white homelessness decreased by 31 percent.lxxv In fact, between 2013 and 2015, the increase in the number of Black homeless persons outpaced the growth of the entire homeless population in the City of Los Angeles, with 3,168 additional Black homeless people and 2,693 homeless persons overall. For the entire city, the odds of being homeless in Los Angeles are 1 in 221. For Black men, the odds are 1 in 28. For Black women, the odds are 1 in 88. In general, Black residents of Los Angeles are nine times more likely to be homeless than others.

FIGURE 4: ODDS OF EXPERIENCING HOMELESSNESS AFTER FOSTER CARElxviii

FIGURE 5: RACE & HOMELESSNESS IN LOS ANGELESlxxii

THE IMPERATIVE

Today, we face a real estate market that is not favorable to the development of affordable housing options for families living on the brink of poverty. Rents are at historic highs and with meager subsidies and high costs for new construction, the community of affordable housing developers have struggled to keep pace with the demand for affordable housing. Within the current housing market, individuals face many barriers to securing housing that they can afford. Renters often need good economic credit to compete for limited housing, yet credit scores are still rebounding after a long recession and a slow recovery. For many communities that were rich in affordable housing options, the forces of gentrification and displacement have forced families to leave neighborhoods in which they have established ties.lxxvi

Despite long-standing policies against discrimination on the basis of race, people of color often face barriers to renting based solely on their race or ethnicity. For those with a previous conviction history,the prospect of finding housing may become impossible.

Moreover, discrimination in the housing sector continues unchecked. Despite long-standing policies against discrimination on the basis of race, people of color often face barriers to renting based solely on their race or ethnicity. For those with previous financial problems, foreclosure, bankruptcy, or eviction may make it challenging to find housing. For those with a previous conviction history, the prospect of finding housing may become impossible. For example, those with conviction histories may lose access to publicly funded housing.lxxvii Even as Los Angeles has prioritized ending veterans’ homelessness, a dishonorable discharge or a previous conviction may make them ineligible for the wave of resources flooding Los Angeles. Over 100,000 veterans left their time of service with an “other-than-honorable” discharge, which can impact their ability to access benefits for the rest of their lives.lxxviii

OPPORTUNITIES FOR CHANGE

In Los Angeles, we are in an unprecedented era. With homelessness at crisis proportions, the media has kept the issue at the forefront of a public dialogue. However, the conversation about homelessness cannot only happen in the media or in City Hall, it must include everyone. We need to have conversations about poverty, race, domestic violence, and foster youth with our families, with our friends, in our churches, and in our labor unions. Without public outcry, the city would not be in the position we are today with active collaboration between the City and County and on the brink of securing sustained investment. We need to hear a call to action that homelessness is unacceptable in our neighborhoods. We need to hear a desire for solutions, that today those without homes are our neighbors, our family members, and without a strong safety net, they could be us.

Additionally, we need to have a substantive conversation on the decades of deliberate policy choices that led to this crisis. Without a focus on the root causes of homelessness the proposals produced may miss important elements that contribute to the crisis. Thus far, proposed solutions have focused primarily on the lack of affordable housing options. This is the obvious solution when homelessness is defined solely as a lack of housing. However, poverty, racism, lack of employment, addiction, mental illness, domestic violence, and being a foster youth are all contributors to homelessness that housing alone will not address. Research at the Economic Roundtable suggests that, “housing alone will not provide a solution until the pathways into homelessness are narrowed… Employment and prevention are the foundation for an effective response to homelessness.”lxxix Increasing affordable housing is essential and undeniable solution, yet there is more to be done.

Citywide comprehensive plans need to include a wraparound approach, focus on the root causes of poverty, and prioritize communities that are more vulnerable to falling into homelessness. We need to move toward best practices in the field which include:

- A multitude of housing options for people at all income levels throughout the City

- Sustained outreach for the chronically homeless

- Strong anti discrimination policies and enforcement of these policies

- Permanent supportive housing for those with disabilities and disabling conditions

- Legal aid for those facing eviction

- Employment programs that connect residents to jobs with a living wage

- Prevention and diversion programs for those at risk of homelessness

- Support for victims of domestic violence

- Rapid rehousing of individuals and families who have been pushed into homelessness

- Supportive services for those with mental illness, substance abuse, or financial crisis

There is a need to fund case managers, outreach workers, and creativity of service providers on the ground to continue to build relationships, offer support as people transition from the streets to housing, and to continue to refine best practices and service unique communities that may not fit within the demographic characteristics discussed in this paper.

As Chair of the Homelessness and Poverty Committee in the Los Angeles City Council, I will focus on utilizing City resources to strategically invest in the people suffering from the homelessness crisis. In January, we released a Strategic Plan that out lines the projected housing deficit and includes some strategies for ending homelessness. This plan will not create change overnight, nor does the city have the financial resources to build its way out of this crisis. Only through a sustained investment and political will can we see change. My committee will (1) pinpoint the opportunities we have to leverage our resources, (2) focus on the areas in which the City has authority, and (3) partner with the County of Los Angeles to create comprehensive policies that will combat decades of poor leadership and policy choices at the State and Federal level.

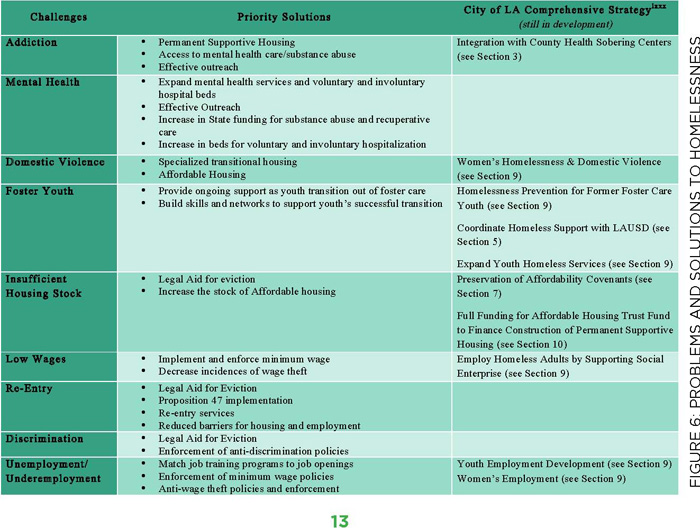

Partnership with State and Federal decision makers is crucial to substantially impacting the flow of people into homelessness. For example, this paper mentions mental health and prisons as major antecedents of homelessness. However, the City has little impact on those systems. The authority for public mental health care and prisons lies with the County of Los Angeles. Additionally, changes to housing policies, like Costa-Hawkins and the Ellis Act, must be made in Sacramento. Further, there is a substantial need for new vouchers to assist homeless individuals and families with the high cost of rent in Los Angeles, however, the federal government has primary jurisdiction over Section 8 vouchers. Elected officials must work in tandem to correct these detrimental systems. The Office will also focus on those areas of homelessness that have yet to rise to the forefront of the discourse, like race and concentrated poverty. Figure 6 details some of the root causes of homelessness and some solutions that can begin to target populations at highest risk of homelessness. Also included are policies from the City of Los Angeles that address these challenges. Figure 6 demonstrates that we have more work to do. The City, as it should, focused on systems and structures that will support effective and efficient use of tax dollars, so that residents can have confidence that an investment in addressing homelessness will be spent wisely and intentionally.

photo by Skidrobot

ENDNOTES

Howard, D. (2008). Unsheltered: A Report on Homelessness in South Los Angeles. Retrieved from: http://www.ssg.org/wp-content/ uploads/Unsheltered_Report.pdf

ii Waldron, T. (2012). The African-American Unemployment Crisis Continues. Retrieved from: http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2012/11/03/1129721/african-american-unemployment-crisis/

iii Waldron, T. (2012). The African-American Unemployment Crisis Continues. Retrieved from: http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2012/11/03/1129721/african-american-unemployment-crisis/

iv Flamming, D. & Burns, P. (2015). All Alone: Antecedents of Chronic Homelessness. Retrieved from: http://economicrt.org/publication/all-alone/

v Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (2015). 2015 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Results. Retrieved from: http://documents.lahsa.org/Planning/homelesscount/2015/factsheet/LACounty.pdf

vi Flamming, D. & Burns, P. (2015). All Alone: Antecedents of Chronic Homelessness. Retrieved from: http://economicrt.org/publication/all-alone/

vii Wagner and White (2014). “Breaking the Silence: Homelessness and Race” in The Routledge Handbook of Poverty in the United States. Eds. Haymes, et al.

viii Ingram, H. & Schneider A. (2005). Public Policy and the Social Construction of Deservedness. Deserving and Entitled. Eds. Ingram, H. & Schneider A.

ix Pew Research Center (2015). The American Middle Class is Losing Ground. Retrieved from: http://www.pewsocialtrends. org/2015/12/09/the-american-middle-class-is-losing-ground/

x Lyons, R. (1984, October 30). How Release of Mental Patients Began. The New York Times. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes. com/1984/10/30/science/how-release-of-mental-patients-began.html?pagewanted=all

xi State of California (2013).http://www.dsh.ca.gov/jobs/psychiatry-flyers.asp Note: Totals estimated from numbers provided by the state as of January 2013. The following facilities reported the succeeding totals. Atascadero – 1072; Coalinga – 1050; Metro – 635; Napa – 1183; Patton – 1378; Salinas – 339; and Vacaville – 388.

xii Lyons, R. (1984, October 30). How Release of Mental Patients Began. The New York Times. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes. com/1984/10/30/science/how-release-of-mental-patients-began.html?pagewanted=all

xiii Lyons, R. (1984, October 30). How Release of Mental Patients Began. The New York Times. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes. com/1984/10/30/science/how-release-of-mental-patients-began.html?pagewanted=all

xiv Coalition for the Homeless (2015). Why Are So Many People Homeless? Retrieved from: http://www.coalitionforthehomeless.org/ the-catastrophe-of-homelessness/why-are-so-many-people-homeless/

xv Weinberger, D. (1999). The Causes of Homelessness in America. Journals on Poverty and Prejudice. S. I. Retrieved from: https://web. stanford.edu/class/e297c/poverty_prejudice/soc_sec/hcauses.htm

xvi Leopold, J. et al (2015). The Housing Affordability Gap for Extremely Low-Income Renters in 2013. Retrieved from: http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/2000260-The-Housing-Affordability-Gap-for-Extremely-Low-Income-Renters-2013.pdf

xvii Leopold, J. et al (2015). The Housing Affordability Gap for Extremely Low-Income Renters in 2013. Retrieved from: http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/2000260-The-Housing-Affordability-Gap-for-Extremely-Low-Income-Renters-2013.pdf

xviii Wagner and White (2014). “Breaking the Silence: Homelessness and Race” in The Routledge Handbook of Poverty in the United States. Eds. Haymes, et al.

xix Henry, M. et al (2015). The 2015 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Retrieved from: https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2015-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

xx Henry, M. et al (2015). The 2015 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Retrieved from: https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2015-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

xxi Henry, M. et al (2015). The 2015 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Retrieved from: https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2015-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

xxii Alamo, C. & Uhler, M. (2015). California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences. Retrieved from: http://www.lao.ca.gov/

reports/2015/finance/housing-costs/housing-costs.aspx

xxiii Alamo, C. & Uhler, M. (2015). California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences. Retrieved from: http://www.lao.ca.gov/

reports/2015/finance/housing-costs/housing-costs.aspx

xxiv Grabar, H. (2015, April 5). The Incredible Shrinking Megacity: How Los Angeles Engineered a Housing Crisis. Salon. Retrieved from:

http://www.salon.com/2015/04/05/the_incredible_shrinking_megacity_how_los_angeles_enginereed_a_housing_crisis/

xxv Bergman, B. (2015, January 15). LA Residents Need to Make $33 Dollar an Hour to Afford the Average Apartment. Retrieved from:

http://www.scpr.org/blogs/economy/2015/01/15/17806/la-residents-need-to-make-34-an-hour-to-afford-ave/

xxvi Wattles, J. (2015, June 14). Los Angeles is Now the Largest City with $15 Minimum Wage. CNN Money. Retrieved from: http://money.cnn.com/2015/06/14/news/economy/los-angeles-minimum-wage-15-garcetti/

xxvii U.S. Census Bureau. (2016). County Quickfacts: Los Angeles County, CA. Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov Note: Percentage includes a proportional percentage of the $50-74,000 income bracket.

xxviii Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce (2008). History of Downtown Los Angeles’ “Skid Row”. Retrieved from: http://www.lachamber. com/clientuploads/LUCH_committee/102208_History_of_Skid_Row.pdf

xxix Skid Row Housing Trust (2012). 25 Years of Ending Homelessness. http://skidrow.org/about/history/

xxx Riccitiello, D. (2013). Report to Governing Board on Annual Progress through 2012 and Ongoing CRA/LA Efforts towards Implementing the Wiggins Settlement Agreement. Retrieved from: http://www.crala.org/internet-site/Meetings/Board_Agenda_2013/ upload/Feb_7_2013_item_7.pdf

xxxi Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce (2008). History of Downtown Los Angeles’ “Skid Row”. Retrieved from: http://www.lachamber. com/clientuploads/LUCH_committee/102208_History_of_Skid_Row.pdf

xxxii Wilcox, G. (August 3, 2007). Foreclosure rate jumps 800 percent in California. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved from: http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2007-08-03/news/0708010748_1_foreclosure-process-homeowners-face-foreclosure-los-angeles-county

xxxiii U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (2002). HUD Releases Report: Discrimination in Metropolitan Housing Markets 1989-2000. Retrieved from: http://archives.hud.gov/news/2002/pr02-138.cfm

xxxiv U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (2002). HUD Releases Report: Discrimination in Metropolitan Housing Markets 1989-2000. Retrieved from: http://archives.hud.gov/news/2002/pr02-138.cfm

xxxv U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (2002). HUD Releases Report: Discrimination in Metropolitan Housing Markets 1989-2000. Retrieved from: http://archives.hud.gov/news/2002/pr02-138.cfm

xxxvi U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (2002). HUD Releases Report: Discrimination in Metropolitan Housing Markets 1989-2000. Retrieved from: http://archives.hud.gov/news/2002/pr02-138.cfm

xxxvii Savage, C. (2012, July 12). Wells Fargo Will Settle Mortgage Bias Charges. The New York Times. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/13/business/wells-fargo-to-settle-mortgage-discrimination-charges.html?_r=0

xxxviii United States Department of Justice (2015, June 22). Justice Department Reaches $335 Million Settlement to Resolve Allegations of Lending Discrimination by Countrywide Financial Corporation. Retrieved from: http://www.justice.gov/usao-cdca/dojcountrywide-settlement-information

xxxix United States Conference of Mayors (2014). Hunger and Homelessness Survey.

xl Bender, A. et al (2015) Not Just a Ferguson Problem: How Traffic Courts Drive Inequality in California. Retrieved from: http://www.lccr. com/wp-content/uploads/Not-Just-a-Ferguson-Problem-How-Traffic-Courts-Drive-Inequality-in-California-4.20.15.pdf

xli Khimm, S. (2013, November 22). Homelessness Drops for the Fourth Year Straight. MSNBC. Retrieved from: http://www.msnbc.com/ all/how-help-the-homeless

xlii https://www.cbo.gov/publication/42754

xliii Khimm, S. (2013, November 22). Homelessness Drops for the Fourth Year Straight. MSNBC. Retrieved from: http://www.msnbc. com/all/how-help-the-homeless

xliv Rosen, R. (2001, February 18). State of Neglect. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved from: http://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/resources/mental-health-law/more-on-mental-health-laws/556-editorial-californias-30-year-failure-to-confront-mental-illness

xlv Rosen, R. (2001, February 18). State of Neglect. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved from: http://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/resources/mental-health-law/more-on-mental-health-laws/556-editorial-californias-30-year-failure-to-confront-mental-illness

xlvi Winarski, J. (1998). Implementing Interventions for Homeless Individuals with Co-Occurring Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders. Retrieved from: http://www.namhpac.org/PDFs/SAMHSAcoocurring.pdf

xlvii Culhane, D. (2015). The 2014 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress PART 2: Estimates of Homelessness in the United States. Retrieved from: https://www.hudexchange.info/onecpd/assets/File/2014-AHAR-Part-2.pdf

xlviii Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (2015). 2015 City of Los Angeles Fact Sheet. Retrieved from: http://documents.lahsa.org/ Planning/homelesscount/2015/factsheet/LACity.pdf

xlix National Institute on Drug Abuse (2014). Principles of Drug Abuse Treatment for Criminal Justice Populations - A Research-Based Guide. Retrieved from: http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-drug-abuse-treatment-criminal-justice-populations/principles

l National Coalition for the Homeless. (2009). Substance Abuse and Homelessness. Retrieved from: http://www.nationalhomeless.org/ factsheets/addiction.pdf

li Blasco, A. (2011). Incarceration and Homelessness. Retrieved from: http://www.endhomelessness.org/blog/entry/incarceration-and-homelessness#.VnMNOPkrKM8

lii The Sentencing Project (2001) Drug Policy and the Criminal Justice System. Retrieved from: http://www.prisonpolicy.org/scans/ sp/5047.pdf

liii Gunja, F. (2003). Race and the War on Drugs. Retrieved from: https://www.aclu.org/files/FilesPDFs/ACF4F34.pdf

liv Blasco, A. (2011). Incarceration and Homelessness. Retrieved from: http://www.endhomelessness.org/blog/entry/incarceration-and-homelessness#.VnMNOPkrKM8

lv Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (2015). 2015 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Results. Retrieved from: http://www. lahsa.org/homelesscount-results

lvi Henry, M. et al (2015). The 2015 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Retrieved from: https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2015-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

lvii Henry, M. et al (2015). The 2015 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Retrieved from: https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2015-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

lviii Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (2015). 2015 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Results. Retrieved from: http://www. lahsa.org/homelesscount-results

lix Grad, S. & Holland, G. (2015, September 22) How Los Angeles’ Homeless Crisis Got So Bad. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from: http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-how-los-angeles-homeless-crisis-got-so-bad-20150922-story.html

lx Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (2015). 2015 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Results. Retrieved from: http://www. lahsa.org/homelesscount-results

lxi Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (2015). 2015 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Results. Retrieved from: http://www. lahsa.org/homelesscount-results

lxii Bekiempis, V. (2014, February 28). Nearly 1 In 5 Americans Suffers From Mental Illness Each Year. Newsweek. Retrieved from:

http://www.newsweek.com/nearly-1-5-americans-suffer-mental-illness-each-year-230608

lxiii ACLU Women’s Rights Project (2008). Domestic Violence and Homelessness. Retrieved from: https://www.aclu.org/files/pdfs/ womensrights/factsheet_homelessness_2008.pdf

lxiv National Network to End Domestic Violence (2010). Domestic Violence, Housing, and Homelessness. Retrieved from: http://nnedv. org/downloads/Policy/NNEDV_DVHousing__factsheet.pdf

lxv Culhane, D. (2015). The 2014 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress PART 2: Estimates of Homelessness in the United States. Retrieved from: https://www.hudexchange.info/onecpd/assets/File/2014-AHAR-Part-2.pdf

lxvi U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (2013). What About Transitional Housing? Retrieved from: https://www.

hudexchange.info/news/snaps-weekly-focus-what-about-transitional-housing/

lxvii Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (2015). 2015 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Results. Retrieved from: http://documents.lahsa.org/Planning/homelesscount/2015/factsheet/LACounty.pdf

lxviii Shah, S. et al (2015). Youth at Risk of Homelessness. Retrieved from: https://www.dshs.wa.gov/sites/default/files/SESA/rda/documents/research-7-106.pdf

lxix Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (2015). 2015 Greater Los Angeles Youth Count Report. Retrieved from: http://documents.lahsa.org/Planning/homelesscount/2015/YouthCountReport.pdf

lxx Courtney, M. et al. (2011). Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth. Retrieved from: http://www.chapinhall.org/research/inside/predictors-homelessness-during-transition-foster-care-adulthood

lxxi Shah, S. et al (2015). Youth at Risk of Homelessness. Retrieved from: https://www.dshs.wa.gov/sites/default/files/SESA/rda/documents/research-7-106.pdf

lxxii Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (2015). 2015 Greater City of Los Angeles Count. Retrieved from: http://documents.lahsa.org/Planning/homelesscount/2015/factsheet/LACity.pdf

lxxiii Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (2015). 2015 Greater Los Angeles Count – Council District 8 Report. Retrieved from:

http://documents.lahsa.org/Planning/homelesscount/2015/factsheet/CD/CouncilDistrict8.pdf

lxxiv Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (2015). 2015 Greater Los Angeles Count – Council District 8 Report. Retrieved from:

http://documents.lahsa.org/Planning/homelesscount/2015/factsheet/CD/CouncilDistrict8.pdf

lxxv Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (2015). 2015 Greater City of Los Angeles Count. Retrieved from: http://documents.lahsa.org/Planning/homelesscount/2015/factsheet/LACity.pdf

lxxvi Scholars Strategy Network (2014, August 20). How “Gentrification” In American Cities Maintains Racial Inequality And Segregation. Retrieved from: http://journalistsresource.org/studies/society/race-society/gentrification-american-cities-racial-inequality-segregation-research-brief

lxxvii Reilly, B. (2013). Communities, Evictions, and Criminal Convictions. Retrieved at: https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/media/publications/convicted_ppl_mvmnt_evictions_and_convictions_report_2013.pdf

lxviii Martin, R. (2013, December 16). Help Is Hard To Get For Veterans After A Bad Discharge. Retrieved from: http://www.npr. org/2013/12/08/249452852/help-is-hard-to-get-for-veterans-after-a-bad-discharge

lxxix Flamming, D. & Burns, P. (2015). All Alone: Antecedents of Chronic Homelessness. Retrieved from: http://economicrt.org/publication/all-alone/

lxxx Los Angeles City Council (2016). Comprehensive Homeless Strategy. Retrieved from: https://cityclerk.lacity.org/lacityclerkcon

nect/index.cfm?fa=ccfi.viewrecord&cfnumber=15-1138-S1